The month, we’re donating 25% of proceeds from sales of Guilt and Mission to Madagascar to Charleston’s Keep Your Faith Corporation. In this blog post, author David H. Mould explores the history of slavery in the British Empire.

Black History Month has given me reason to reflect on the history of slavery in Britain, the country where I was born and lived until my late twenties.

Recently, the legacy of slavery and the issue of reparations to descendants of slaves has become a major topic of public and political debate. Universities, museums and corporations have been critically re-examining their own histories. Were their founders or benefactors slaveowners? Or did they, like the merchants and shipowners of London, Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow, benefit indirectly through transporting slaves or the products of plantations? What is their modern-day responsibility for the acts of the past?

Universities have established slavery research centers and grants for graduate students from communities of color, corporations have invested in diversity and community development programs. Statues of leading citizens connected to the slave trade have come tumbling down. Descendants of former slaveowners have come forward to offer apologies and, in some cases, financial restitution.

Most of this history was new to me. If anything about Britain’s slave trade and plantation economies was in the school curriculum in the 1960s, it was buried under the weight of all those kings, queens, prime ministers, battles, treaties and acts of parliament whose deeds and misdeeds I had to regurgitate on tests.

For centuries, the major colonial powers—the British, French, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese—had engaged in an expanding slave trade from Africa to supply labor for their plantation colonies in the Caribbean and South America. In every country there was opposition to slavery on moral grounds, but economic interests always prevailed.

In 1794, in a radical social reform by France’s new revolutionary regime, slavery was abolished. However, it was impossible to enforce the ban in the Caribbean colonies, where plantation owners threatened to secede to Britain where slavery was still legal. Slaves in Haiti rebelled and overthrew the French regime, but slavery remained in France’s other Caribbean colonies.

After a long and well-financed campaign from the abolitionist movement, Britain became the first colonial power to ban the slave trade by act of parliament in 1807. The act did nothing to help those who were already enslaved. Economic interests again prevailed: to abolish slavery without importing a new labor force to the plantations would have spelled financial disaster, both for the owners and for Britain’s commercial and financial markets.

It was more than a quarter century later, in 1834, that Britain abolished slavery in its colonies. For most slaves, “freedom” was a technical change in legal status; most became indentured laborers and saw little improvement in their living conditions. And the slaveowners were handsomely reimbursed for what was called their “loss of property.”

When British and Americans think about the slave trade, they naturally focus on the transatlantic traffic from Africa to the Americas—to the United States, the Caribbean, and South America. It was not until I began research for Mission to Madagascar: The Sergeant, the King, and the Slave Trade that I began to understand that the slave trade was a global phenomenon.

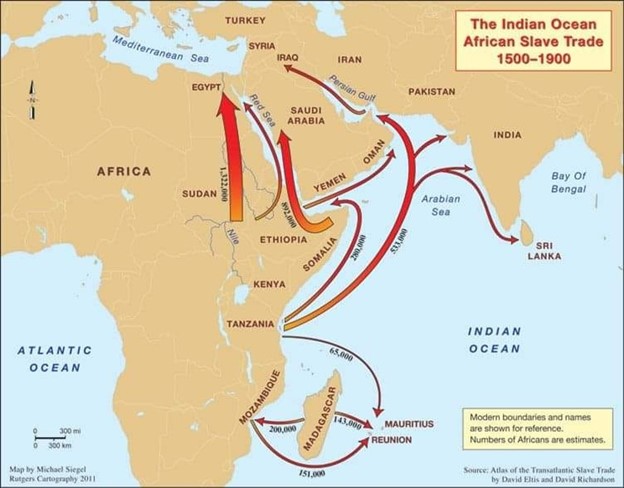

Slavery had existed in African societies for thousands of years. People, especially those without a family to protect them, were bought, sold, exchanged, or used to settle a debt. Captives taken in wars between tribes were ransomed to their relatives. Then the Arab traders arrived on the east coast of Africa and turned the local slave trade into an international business, with established supply routes and lines of credit for commercial goods to purchase slaves.

The traders found willing partners in the tribes of the heavily populated Great Lakes region, a vast area that now comprises parts of western Kenya and Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Malawi, and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Tribes raided villages, seizing men, women, and children. They exchanged them for the currency of the period—cloth goods imported from India, brass wire, beads, muskets, and gunpowder. With their guns, they took territory from weaker tribes and seized their cattle. When the supply of war captives dried up, they would find a pretext to start a new conflict.

The traders assembled caravans of up to 1,000 slaves to march hundreds of miles to the coast, with bands of armed tribesmen to protect them from raids by local tribes. The traffic in slaves went hand in hand with the lucrative ivory trade, with male slaves carrying huge elephant tusks. The main entrepot was the island of Zanzibar, ruled by a dynasty from the Arabian Peninsula. From Zanzibar, their dhows carried slaves north to the markets of Arabia, Persia and India.

Southeast of Zanzibar, the plantation economies of the islands of Mauritius and Bourbon (today Réunion) in the southwest Indian Ocean were completely dependent on slave labor. Where did the slaves come from? Most were shipped from the island of Madagascar.

For centuries, warring clans had stolen cattle and taken war captives, who were ransomed to their families or kept as slaves. The arrival of French slave traders in the 18th century opened a new and lucrative market for captives. On the northwest coast, Arab traders shipped slaves captured in the interior across the Mozambique Channel. Some were marched to slave markets in the central highlands or to east coast ports for shipment to Mauritius and Bourbon, others sent north to Zanzibar.

Mission to Madagascar, based on primary sources, recounts an almost forgotten chapter in the history of the global slave trade. Without enough naval ships to patrol the seas to stop smuggling, or the troops to mount an invasion, the governor of Mauritius, seized from the French during the Napoleonic Wars, opted for a diplomatic strategy. He decided to try to persuade Radama, the young, impetuous and warlike ruler of the rising military power in the island, to conclude a treaty to halt the export of slaves.

The unlikely hero of the story is James Hastie, a 30-year-old East India Company sergeant with no diplomatic experience, dispatched in 1817 to travel to Radama’s court. His journals recount how he used his wits and persuasive powers to win over the king who faced strong opposition from nobles, army commanders and clan chieftains who profited from the sale of slaves.

The treaty ending the slave trade from Madagascar came at a price. Just as the British government later compensated the plantation owners of the Caribbean for their “loss of property,” the governor agreed to recompense Radama for his loss. The British trained his army, provided him with the muskets and gunpowder he needed to subdue rival clans, and recognized him as king of the whole island.

The moral victory of ending the slave trade was tempered by political and economic expediency. Britain secured a powerful ally, kept the French out of Madagascar and gained favorable tariffs for its trading ships. Meanwhile, the internal slave trade in Madagascar continued unabated.